Milo Edwards, a BA Education Studies student, reflects on their summer research fellowship with Generation UCL.

About the Fellowship

This summer I embarked on a new Department of Education, Practice and Society Undergraduate Research Fellowship (EPSURF) under the supervision of Georgina Brewis. This was an amazing opportunity to work on a small part of Georgina’s wider research project, Generation UCL. Generation UCL explores the student experiences of UCL since its founding nearly 200 years ago. My research fellowship centred around the exploration of UCL’s queer history, specifically from the perspective of students in the 1970s.

In my first meeting with Georgina, we discussed the online resources already available on UCL’s queer history and decided I would write a report summarising them, so they could all be available in one document. As I listened to podcasts and read accounts of UCL’s LGBT histories I was surprised to discover so many stories from the 1970s and earlier, due to the amount of discrimination the LGBT community faced (especially before the partial decriminalisation of male homosexuality in 1967).

Writing the Report

However, it was also clear that there were gaps in the histories where it was difficult to say exactly how people felt and what certain relationships were like. I think this is where the development of language must be taken into consideration. While today there are many labels available to people of all sexualities and genders, due to the lack of public discussion in LGBT history, those labels seem to be either lacking or contain a different set of connotations as they would normally today. This became clear to me while listening to a podcast made by Slade alumnus Derek Jarman for UCL when he talked about what ‘queer’ meant to him then and now. In this way, understanding the LGBT history was difficult in areas, as I did not want to suggest UCL alumni had LGBT experiences without evidence, but there was little explicit evidence before the 1970s.

After completing the report on information that was already available online, Georgina and I noted that there was relatively little research done by historians on UCL’s LGBT history. As I had limited experience of archives that were not digitised, I assumed that was the end of my research journey and concluded that there were not enough archives available on this topic. As a professional historian, Georgina was not satisfied with this conclusion, and fortunately directed me towards UCL Special Collections!

Visiting UCL Special Collections

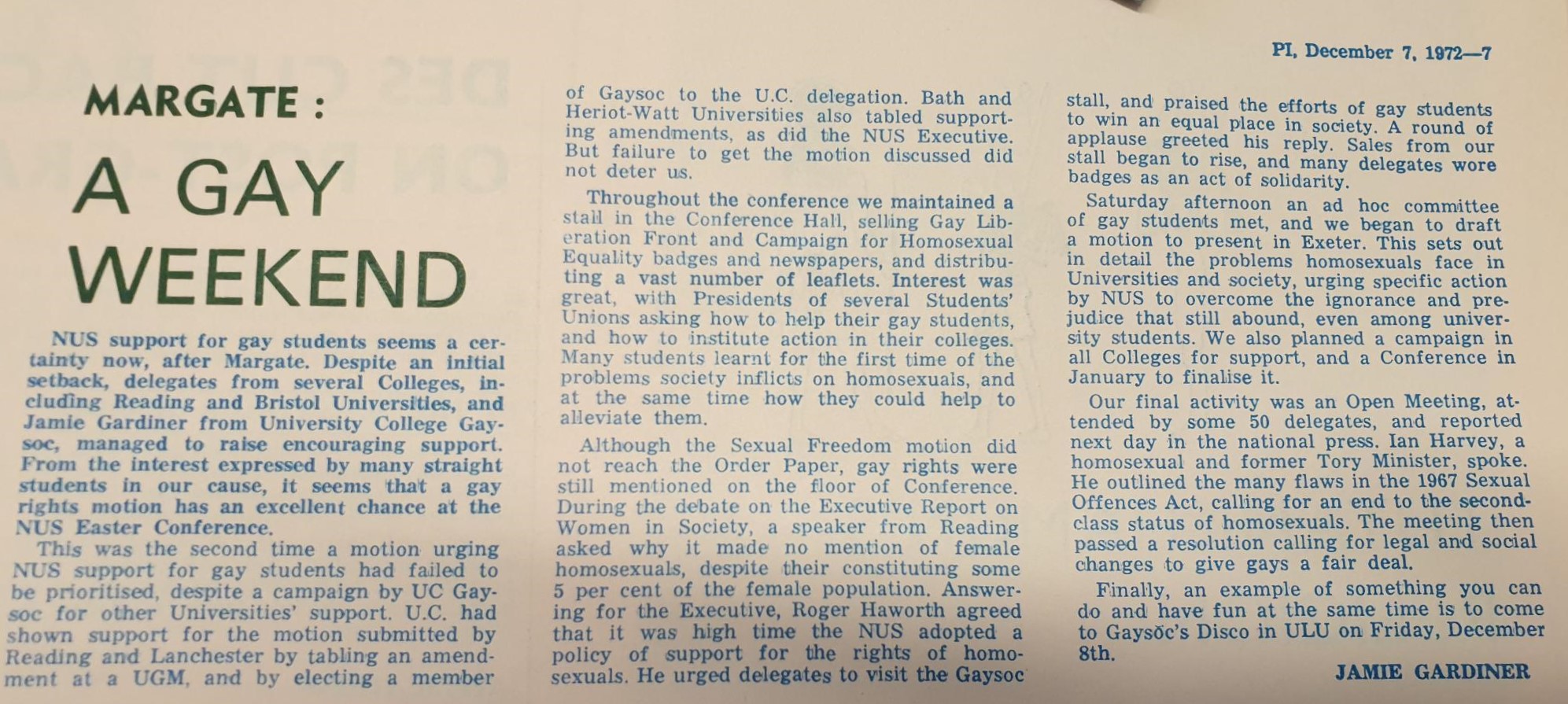

I can only describe UCL Special Collections as a treasure trove of information, and myself as an LGBT scavenger on my visit there. I was amazed to find how easy it was to arrange an appointment and on entry as I set my eyes on the ten or so boxes of files from UCL’s history potentially holding the answers to my questions, I felt both a sense of intimidation and excitement about the several hours to follow. During that time, I scoured student handbooks, Pi newspapers and GaySoc files for as much information as I could find, feeling grossly under-qualified, but also extremely privileged to access the archives in front of me. Ultimately, I found some insightful information about what it might have been like as an LGBT student in the 1970s, and I felt a lot closer to the history I had been researching. I would say this was the highlight of my experience as an EPSURF!

Reflections

However, my experience at UCL Special Collections also made me aware of the LGBT histories that have not yet been discovered in the archives. I did not spend a lot of time at the UCL Special Collections, and I am not a historian, yet I found LGBT histories, which have not yet been researched and written about. So, I think if someone were commissioned to research the queer histories of UCL they would find a lot more, which would not only contribute to UCL’s history, but to current queer students’ sense of belonging at UCL.