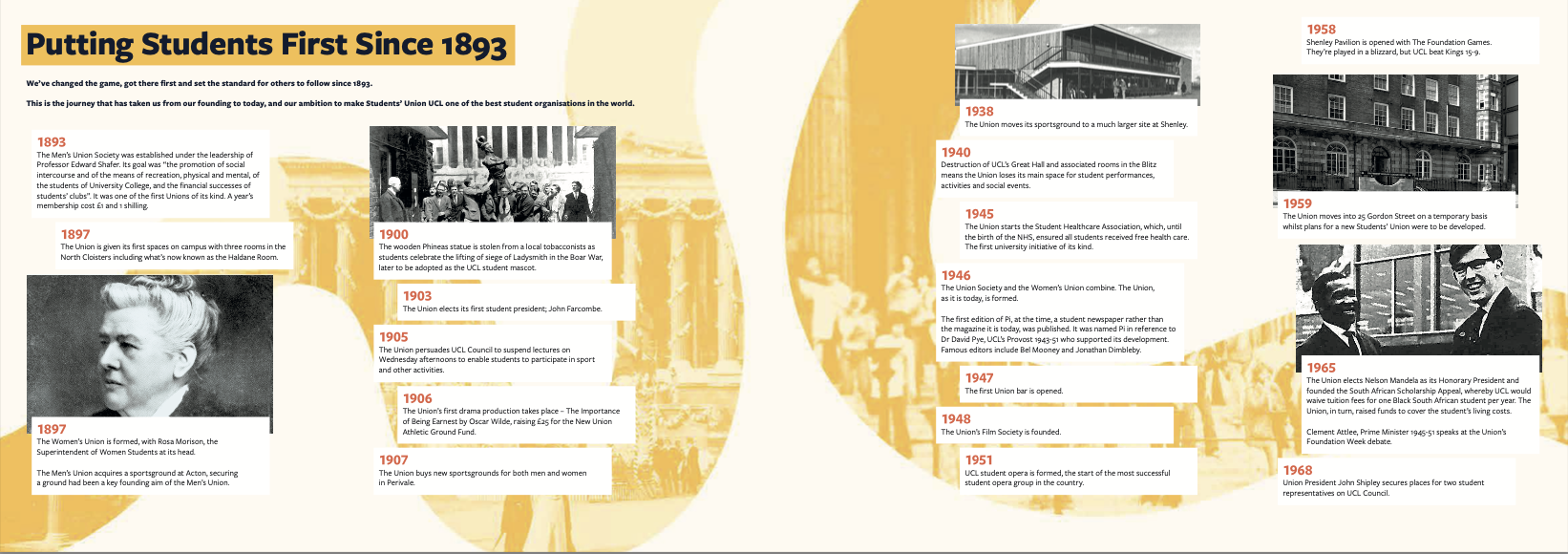

On the third of June 1893, UCL's Council approved the formation of the Men's Union Society for ‘the promotion of social intercourse and of the means of recreation, physical and mental, of the students of the University College, and the financial success of students’ clubs’. This was the first version of a Students' Union at UCL and in September 1893 the first students joined the society, starting a 130-year journey to the students' union you know today.

Over the coming months we'll be sharing more on the history of the Union and celebrating the impact we've made over the past 130 years.

To kick off the start of our 130 year anniversary, Dr. Sam Blaxland, Generation UCL Research Fellow, has shed light on the formation and early years of the Union...

1893 is certainly a legitimate year to think about the birth of Students’ Union UCL. As with much history, however, the reality is a bit more complicated. On one hand, the unofficial beginnings of the organisation stretch further back in time. On the other, 1893 marked the founding of the men’s union only, from which women were excluded.

What we now know as UCL was founded on 11 February 1826, as a non-sectarian institution. It would go on to admit non-conformists, Roman Catholics, Jewish people and – later – women. As the original ‘University of London’, it opened its doors to a first cohort of students in October 1828. Much of the building was incomplete. Medical students dominated the first cohorts and a Medical Society, that looked a bit like a students’ union, was formed immediately. In the same year, a Debating Society was set up (although it was originally named the Literary and Philosophical Society).

There was even some kind of student press in this earlier period. Such publications would later be considered a key element of Union life. However, early examples like the London University Chronicle, published in 1830, or the UCL Gazette only lasted for a few editions. Even in these earliest newspapers, students were not shy about criticising the College authorities, showing that there has long been a rebellious and independently-minded streak amongst UCL students.

A variety of other student societies existed before 1893, some of which acted as forerunners of the Union. A Reading Room Society was formed in 1858 with the primary aim of encouraging a greater sense of community amongst students. At this stage, men and women had separate spaces on campus, but UCL did have a good record of admitting female students. They had their own societies, too, such as the Women’s Debating Society, formed in 1879. In 1884, the University College Society, was founded. Its aim was to maintain friendly relationships between the College, its staff and students. The University College Gazette becomes the first systematic student publication at the same time.

Much of this paved the way for the Men’s Union Society, formed in 1893 as a co-ordinating body for athletic clubs and wider social activity. A desire for better sporting facilities and a more suitable athletics ground were a major driving factor behind this and a ground at Acton was purchased in 1897. The Men’s Union’s stated aim was ‘the promotion of social intercourse and of the means of recreation, physical and mental, of the students of the University College, and the financial success of students’ clubs’. In that first year, there were 133 members, amounting to about 10 per cent of the student population. The Men’s Union represented what most Students’ Unions across the country would eventually become, but UCL’s Union was the first to bring these elements of student life together under one umbrella, making it genuinely pioneering.

Women, however, were not included in the Union. Several years later in 1897, a separate Women’s Union was formed. This was done under the guidance of Rosa Morison, the Lady Superintendent of Women Students and a pivotal figure in the suffrage movement at UCL.

1893 is therefore a very important moment in a wider story. Perhaps the next most important period, where so much that defines the contemporary Union came into being, encompasses the immediate post-Second World War years. The spirit of reconstruction and political change across the country after 1945 had a profound impact on many walks of life, and on higher education. UCL – and the Union – were no different.

All students were evacuated from UCL during the war itself – for good reason. The site was heavily bombed during the Blitz. Students and staff returned, however, with a desire to improve life there. Perhaps the most significant thing the Union did was to fuse together the separate men and women’s unions into a joint society in 1948. In that same year the Union appointed Margaret Richards as its Permanent Secretary. She is one of the most important people in the Union’s history, holding the position for 23 years. She was reportedly ‘loved by everyone at UCL’, working very long hours and executing her duties very efficiently. Her guidance helped shape the organisation and set a course for its future direction.

Sport at UCL also entered a new phase, with the sports ground at Shenley coming into use in 1946. The land at Shenley had actually been purchased in 1939 as a replacement for the ground at Perivale. However, before work could begin at the site, war broke out and the fields were used as grazing land for sheep. When they came into operation, the facilities there were better. It had double the number of rugby and soccer pitches, and much better bathroom, changing and bar facilities. An alternative extra-curricular organisation set up at this time was Film Soc., which became one of the ‘associate’ societies that any student could be a member of without paying. Film Soc would quickly develop into a very modern kind of society, fit for the post-war era, but it was also extremely popular with students. Over the years, it produced some of the best student-led films and newsreels at any university in the country.

A spirit of renewal also led to the foundation of a new newspaper, with the aim of giving students back their voice to comment on a range of College activity during a period of bleak post-war austerity and the consequences of bomb damage. It was called Pi, named after the Provost Sir David Pye – an act of deference that was of its time and would not happen now! From the beginning, students engaged with the paper, writing large numbers of letters to it, offering witty comment on College life, or complaining about inadequate facilities (of which, it must be said, there were many). As with all student publications, Pi was written and produced by a relatively tiny number of students, butithas nonetheless been operating in various forms ever since, making it one of the country’s longer-standing student newspapers.

Despite justified complaints about facilities, these immediate post-war years included a decision to open the first Union Bar, with a full-time barman. Opened in 1947, it was situated in the South Junction and did not sell spirits. A few years later, the Union was given a set of rooms in the nearby South Wing basement, which allowed all its offices to be in one place, where they stayed until 1959 when the Union moved to what was deemed to be temporary accommodation at 25 Gordon Street.

Over the coming months we'll share more of our 130 year history as we lead up to the launch of a new History of the Union booklet published in September 2023.

Generation UCL

As UCL starts the countdown to its bicentenary in 2026, a new research and engagement project puts students and alumni at the heart of the history of UCL.

‘Generation UCL’ explores 200 years of student life in London, turning institutional history upside down to suggest that the first students of 1828 should be seen as the real ‘founders’ of UCL.

UCL has shaped the lives of generations of students, and in turn those generations of students have shaped UCL, London and the wider world. Students have played an important role throughout UCL's history and the ‘Generation UCL’ project will help uncover the enormous impact of student culture at UCL through the stories that connect us all.

Generation UCL is led by Professor Georgina Brewis (IOE, UCL’s Faculty of Education and Society) and John Dubber (Students’ Union UCL), with Dr Sam Blaxland as Generation UCL Research Fellow. The project is a partnership between the International Centre for Historical Research in Education at IOE, Students’ Union UCL and the Office of the Vice-President (Advancement).

Follow the project via the link below...